The Christopher Hitchens delight -3

*

Author and journalist Christopher Hitchens has died aged 62 (AP)

Richard Dawkins: Illness made Christopher Hitchens a symbol of the honesty and dignity of atheism

On 7 October, I recorded a long conversation with Christopher Hitchens in Houston, Texas, for the Christmas edition of New Statesman which I was guest-editing.

He looked frail, and his voice was no longer the familiar Richard Burton boom; but, though his body had clearly been diminished by the brutality of cancer, his mind and spirit had not. Just two months before his death, he was still shining his relentless light on uncomfortable truths, still speaking the unspeakable (“The way I put it is this: if you’re writing about the history of the 1930s and the rise of totalitarianism, you can take out the word ‘fascist’, if you want, for Italy, Portugal, Spain, Czechoslovakia and Austria and replace it with ‘extreme-right Catholic party'”), still leading the charge for human freedom and dignity (“The totalitarian, to me, is the enemy – the one that’s absolute, the one that wants control over the inside of your head, not just your actions and your taxes. And the origins of that are theocratic, obviously.

The beginning of that is the idea that there is a supreme leader, or infallible pope, or a chief rabbi, or whatever, who can ventriloquise the divine and tell us what to do”) and still encouraging others to stand up fearlessly for truth and reason (“Stridency is the least you should muster … It’s the shame of your colleagues that they don’t form ranks and say, ‘Listen, we’re going to defend our colleagues from these appalling and obfuscating elements’.”).

The following day, I presented him with an award in my name at the Atheist Alliance International convention, and I can today derive a little comfort from having been able to tell him during the presentation that day how much he meant to those of us who shared his goals.

I told him that he was a man whose name would be joined, in the history of the atheist/secular movement, with those of Bertrand Russell, Robert Ingersoll, Thomas Paine, David Hume. What follows is based on my speech, now sadly turned into the past tense.

Christopher Hitchens was a writer and an orator with a matchless style, commanding a vocabulary and a range of literary and historical allusion far wider than anybody I know. He was a reader whose breadth of reading was simultaneously so deep and comprehensive as to deserve the slightly stuffy word “learned” – except that Christopher was the least stuffy learned person you could ever meet.

He was a debater who would kick the stuffing out of a hapless victim, yet did it with a grace that disarmed his opponent while simultaneously eviscerating him. He was emphatically not of the school that thinks the winner of a debate is he who shouts loudest. His opponents might have shouted and shrieked. Indeed they did. But Hitch didn’t need to shout, for he could rely instead on his words, his polymathic store of facts and allusions, his commanding generalship of the field of discourse, and the forked lightning of his wit.

More at the Belfast Telegraph

Reviewed by Bob Williams

Reviewed by Bob Williams

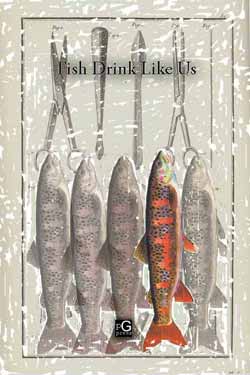

Last Night’s Dream Corrected

Pretend Genius Press

2006, ISBN 0-9747261-6-8, $10.50, 118 pages

This is an anthology of poetry. There are thirty-five poems written by twenty poets. The geographic range is wide. Many are from the large coastal cities of the United States, some are from Europe, and one lives about twenty miles from my home.

Pretend Genius itself requires comment. This is a loose assembly of writers who do serious things but are not themselves notably serious. The level of talent is remarkable. I have all their books and I have never been disappointed in any of them.

An anthology is an unnatural animal. Some of it can do tricks, but some of it can do no more than doze by the fire. The usual inspirational suspects are here. Some of the poets draw on popular culture and some draw on more classical material. Both have the same problem: will the reader catch their drift and allusions? Other poets use the simple language that bridges the gap without allusional obstructions. Plain words work – with the odd adjective or two to dazzle and wake the reader.

The introduction is by Bloog Mandrake. He refuses to discuss the poets. “So what could possibly be said about the poets in this anthology that they might not have already lied about to their mothers?” Instead he writes about readers and poetry. The latter, although not very well, declines to die, and the former can keep it healthy if they will.

As with every anthology, some parts are better than others – or perhaps more readily accessible. Some of ones that are not immediate in their appeal will wait for their time to come, their moment of fusion with a suddenly wakened reader. But the collection makes a strong beginning (as we will see later, it also makes a flourishing end). This is serendipitous since the poems are in alphabetical order. Raewyn Alexander’s three opening poems are very likeable. I especially enjoyed this verse from ‘thunder debates with ice and lightning leads.’

i sleepwalked in the eyes of it

drenched with what used to be promises

your dark ghost loosing new hair

insurance could cover this if it had heart

‘Nostos’ by Stratos Fountoulis is too long to quote and too much of a piece for easy excerpting. It is haunting and distinguished work by a man who modestly claims not to be a poet. He is unquestionably a distinguished artist, designer of many Pretend Genius covers and creator of the artwork.

Not all of the work in this collection is ‘pure’ poetry. Susan Kennedy’s two poems (‘It was the crow you see’ and ‘Proper poems will not be written’) dwell on the ethical meanings that we fasten on the external world or the limits that the proper world tries to fasten on reality. We are treading the dreaded border of the didactic here, but Kennedy is too nimble for such a trap, and these poems combine unusual material with great talent.

And Elias Miller’s two poems (‘death brings different socks’ and ‘God the stepfather’ have some of the same qualities of Kennedy’s evasion of solely poetic purposes. Miller, however, shows himself capable of more bitter-edged meditation.

It is impossible to pass by Dean Strom’s three excellent contributions without notice of his parody, clever and funny, of William Carlos Williams.

Blem Vide’s ‘Art Without Instructions (an art disclaimer)’ presents him at his best. The reader may find this poem as the opening of Vide’s Babble on to Babylon, one of the best books by a new poet that I know of. My favorite lines:

In art as in life – be just.

But if you cannot be just – be arbitrary.

The book closes with a most appropriate poem by Richard Wright (about whom there are no details in Contributors – most mysterious) about poetry.

This is obviously something of a scattergun as a review. I liked much more than I have mentioned and if you are a reader who reads poetry, you will have the same experience. I recommend this book very much.

You my buy “Last Night’s Dream Corrected” at Amazon.com http://www.compulsivereader.com/html/index.php?name=News&file=article&sid=1240

.

.

Cover designed by Stratos

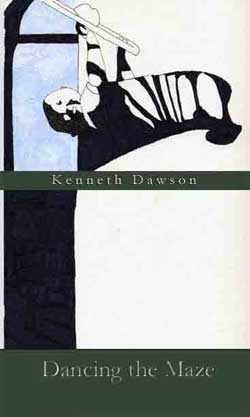

by Kenneth Dawson

by Kenneth Dawson

PretendGenius Press 2004, ISBN 0-9747261-9-2, $9.95, 114 pages

Kenneth Dawson was born in 1957. He has fitfully attended universities but has – in his own words – “escaped without a degree.” His résumé shows a disconnected mélange of military service and employments. This is, it appears, his first book.

Dancing the Maze examines five areas in an approach that it would be difficult to describe as short stories. Events of a specific sort are placed in juxtaposition, some of it is in prose and some of it is poetry. The book is unified by a bleakness of vision that is arresting.

‘Paralysis’ accounts for the early life of a man abused by his father, enfeebled with and turned bitter by a debilitating disease. The protagonist later serves in Vietnam where he is at last rendered numb by the brutality of the war. In the end he creates a kind of private truce and sits oblivious of military protocol. “And I knew secrets. If you’re not willing to shoot them you must be careful with people who know secrets.”

‘The Blues You Play’ stays in the same area of human brutality but the expression is cast in terms of even more remotely connected insights, most of them expressed with the concision of poetry. “If there is a God, is it manifested in the forgiveness of survivors? I think of a woman who lived through My Lai describing horrors in an interview and saying she didn’t hate Americans, but only wondered, why? Perhaps she, transcending hate, is why.”

‘Confession of a Race Traitor’ brings the soldier out of service into a struggle with the equally insane demands of civilian life in a debased and vicious society. The situation, rather than the story for there is none, is built up of comments, descriptions and meditations.

‘Manifest Destiny’ has three parts: an Indian that explodes against the depravity of those that oppress him and goes on a killing spree; an anthropologist who shares his information on an obscure tribe with the military which kills the tribe off for political but essentially trivial reasons; and an Indian shaman who has adopted a fictitious role unknowingly but is led to embrace it as still the best that he can achieve in a sick world.

‘The Great American Desert,’ the short closing piece, is a rhapsody on the deserters from society. Almost all the books that I have been reading lately show a great debt somehow to Kerouac. Since I have never regarded Kerouac as a great or even a good writer, I am happy that all of the writers that I have been reading lately are much better writers than he.

Dawson told me more about human brutality that I want to think about and put my forbearance to the test. Happier writers, if they are any good and not fools, will know that there is much to fear and much to dislike but they seldom bring us reports from the abyss. Dawson does and the honesty of his report wrings admiration from me reluctantly. This is what a book should be as a transfiguring instrument and there is nothing to say that such an experience will be a happy one. Thus warned, every reader will need to meditate on his or her need for such a book. For my part I found it an extraordinary experience which I would not have missed but which I would not want to repeat.

Buy Kenneth Dawson’s book at Amazon.com

http://www.compulsivereader.com/html/index.php?name=News&file=article&sid=736

.

cover designed by Stratos

cover illustrations by the Author

The degree of finish and the form of the meditations vary. Some are stories or almost. Most of them are outpourings of a tormented heart. The author has a very special voice and he aims it at the reader directly and personally.

The degree of finish and the form of the meditations vary. Some are stories or almost. Most of them are outpourings of a tormented heart. The author has a very special voice and he aims it at the reader directly and personally.

Reviewed by Bob Williams

The Baltimore Years

by J. Tyler Blue

PretendGenius Press 2004, ISBN 0-9747261-3-3, $12.95, 145 pages

Baltimore, already graced by novelist Anne Tyler, receives an altogether different homage from J. Tyler Blue in these meditations on drawing breath alone and in pain.

The degree of finish and the form of the meditations vary. Some are stories or almost. Most of them are outpourings of a tormented heart. The author has a very special voice and he aims it at the reader directly and personally. It is a strange feeling to be addressed in this manner by an author and I am not aware that any other author comes close to Blue in this type of communication. A convention to the other authors that have attempted it, to Blue it is a realistic literary form.

Those parts of the book that are not stories or near-stories are poems. By a paradox the poems offer the more objective comments.

This is an entire chapter from The Baltimore Years:

Burning Dear John

I slept today

Or maybe it was yesterday

I don’t know

Heartbeats ceased making sense of time

I scratched out a message to the gods

On another empty match book.

I am mailing it to NASA

To send to the heavens.

“I’ve been missing you since before I knew you were”

She smiled

She said she felt the same way once,

About tea and cigarettes.

Did I see you? “On the stairs?”

I breathed, hoping she would catch it.

Hoping she would before leaving

For the moon.

When the element of story is weak and the style is indisputable prose, the result is a torrent of words as if Blue opened his mind to his word processor in a struggle of creation that becomes the effort to capture the self, to snare the truth in the most rapidly constructed net of words that Blue can manage.

This is a very intimate document with a greater emphasis on truth than beauty. It is also a convincing display of the creative process in action. This makes it startlingly different. Since different is not always a blessing, I must add that it is of exceptionally high quality. Every reader that values probity in a writer and has no fear of the adventurous will want this book.

You can buy the book from Amazon

Review from: http://www.compulsivereader.com/html/index.php?name=News&file=article&sid=735

.

.

cover designed by Stratos

The arrangement of the many stories in Still Life is an adventure in itself. The groupings have titles and the succession is ‘stories about something,’ ‘stories about nothing,’ ‘stories about things that might have happened,’ ‘true stories,’ stories about things that should have happened’ and so onwards with playful ingenuity.

The arrangement of the many stories in Still Life is an adventure in itself. The groupings have titles and the succession is ‘stories about something,’ ‘stories about nothing,’ ‘stories about things that might have happened,’ ‘true stories,’ stories about things that should have happened’ and so onwards with playful ingenuity.

Reviewed by Bob Williams

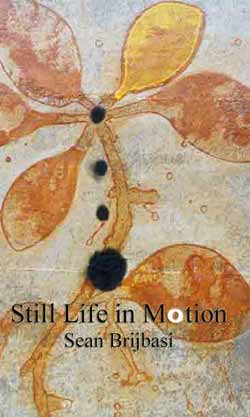

Still Life in Motion

by Sean Brijbasi

PretendGenius Press 2004, ISBN 0-974261-0-9, $14.95, 248 pages

Fiction usually brings us recognizable themes and characters set in a world that we perceive as real. The creation from this of an artistic work involves some manipulation and artificiality. The obtrusiveness of such manipulation will be more or less obvious depending on the skill of the writer but we will tend to accept it even when it makes a spectacle of itself. But there are alternatives.

Brijbasi explores such alternatives. He concerns himself with the irrecoverables of life. These are the small, almost invisible, quirks and reflexes that play on the surface of our minds and actions. Irrecoverables exist at a level prior to character, incident or conflict. Brijbasi is the poet of irrecoverables. The shadowy figures of his skeletal world have no faces and they would not accept epiphanies. They do accept absurdities and they revel in contradictions. Brijbasi carries this to a degree that naturalizes absurdities and contradictions. The result is less fiction than a display of the mechanics of fiction that focuses on the bare minimum of expected content. This austerity, however witty it often is, brings the reader to considerations of what reality might be like if we look at it closely and if it is in fact real.

This is the second book by a young writer. The first and shorter book, One Note Symphonies, appeared three years ago. It already showed a mature polish and acceptance of exotic worlds worthy of report. Still Life is more varied and presents a wider range of ability. There are effects that might elude the reader. For example, in a scene where the protagonist watches television and hears the following, the reader will miss the point unless the reader knows that Brijbasi was born in 1967: “Born in 1967, he went on to do nothing and was remembered by no one.”

But there are constants in Brijbasi’s shifting world. Martin from One Note Symphonies is a frequent actor in Still Life. Sasha from the opening story makes a floating appearance elsewhere before she takes on a more concrete existence towards the end of the book. Martin proves to be a nuisance and Brijbasi kills him off several times (in ‘Minor Character’) only to have him revive and end up in bed with the heroine.

The arrangement of the many stories in Still Life is an adventure in itself. The groupings have titles and the succession is ‘stories about something,’ ‘stories about nothing,’ ‘stories about things that might have happened,’ ‘true stories,’ stories about things that should have happened’ and so onwards with playful ingenuity.

Brijbasi’s playfulness is often displayed with funny and apposite descriptions: “So this girl that I’m meeting tonight, Saturday night, I’ve known for a few years now, but I’m starting to misknow her because, well, it’s hard to admit, but I know that she has been unloving me slowly for the last year or so and I want to crash land like a lullaby in some stripper’s arms.”

In the section entitled ‘Reading Stories’ Brijbasi loiters with intent over academic writing and tests. The satire is loony but exact and a construction of elaborate wit. Too involvedly sustained to quote, it contains such delights as sportscasters commenting on a public reading.

This book is exhilarating in its freedom and its poetry and wit are a constant refreshment. In my review of One Note Symphonies I wondered if such a special talent could survive in today’s glut of books but Still Life indicates that he is a survivor. This is very good news for us all.

To buy the book: look at Still Life in Motion – Amazon.com

http://www.compulsivereader.com/html/index.php?name=News&file=article&sid=672

.

.

….the free wordpress blog.

Well, finally it’s not a good idea having your blog hosted in your own server…it’s a lot inferior in function than that of the free version… its options are more (stats, visits etc. etc.,) + the wide audience. More people read your stuff.

well, vanity.

why not.

As my new work will probably be classified as a New Realism of some kind, though I dislike any classification, I am posting a few words on the whereabouts of this so-called movement…

From: a Centre Pompidou location

Nouveau Rationalisme, New Realism, was founded in October 1960 with a joint declaration whose signatories were Yves Klein, Arman, Francois Dufrêne, Raymond Hains, Pierre Restany, Daniel Spoerri, Jean Tinguely and Jacques de la Villeglé; in 1961 these were joined by César, Mimmo Rotella, then Niki de Saint Phalle and Gerard Deschamps.

Nouveau Rationalisme, New Realism, was founded in October 1960 with a joint declaration whose signatories were Yves Klein, Arman, Francois Dufrêne, Raymond Hains, Pierre Restany, Daniel Spoerri, Jean Tinguely and Jacques de la Villeglé; in 1961 these were joined by César, Mimmo Rotella, then Niki de Saint Phalle and Gerard Deschamps.

These artists declared that they had come together on the basis of a new awareness of their “collective singularity”. For all the diversity of their plastic language, they did indeed perceive a common basis for their work, this being a method of direct appropriation of reality, equivalent, in the terms used by Pierre Restany, to a “poetic recycling of urban, industrial and advertising reality” (60/90. Trente ans de Nouveau Réalisme, La Différence, 1990, p 76).

Their group activity and the exhibitions they mounted together covered the period from 1962 to 1963, but the history of New Realism continued at least up until 1970, the year of the group’s tenth anniversary, which was marked by the organisation of large-scale events.

1962 to 1963, but the history of New Realism continued at least up until 1970, the year of the group’s tenth anniversary, which was marked by the organisation of large-scale events.

Much as this new awareness of a “collective singularity” was decisive, their grouping was clearly motivated by the intervention and the theoretical input of the art critic Pierre Restany. Being first interested by abstract art, he moved towards the elaboration of a sociological aesthetic after his meeting with Klein in 1958, and in large part the group’s theoretical justification was his.

The term Nouveau Réalisme (New Realism) was forged by Pierre Restany during an early group exhibition in May 1960. By returning to “realism” as a category, he was referring to the 19th-century artistic and literary movement which aimed to describe ordinary everyday reality without any idealisation. Yet, this realism was “new”, in the sense that there was a Nouveau Roman in fiction and a New Wave in film: in the first place it connects itself to the new reality deriving from an urban consumer society, in the second place its descriptive mode is also new because it no longer is identified with a representation through the making of an appropriate image, but consists in the presentation of the object chosen by the artist.

It is also thanks to Pierre Restany that New Realism was defended on the international scene in the face of an emerging American art form, Pop Art, and financially supported by a network of dealers and collectors.

up:Raymond Hains, Panneau d’affichage (Billboard), 1960

Torn posters on panel of galvanised sheet metal

200 x 150 cm

bottom: Yves Klein, Monochrome Bleu (Monochrome Blue) (IKB 3), 1960

Pure pigment and synthetic resin on canvas mounted on wood

199 x 153 cm